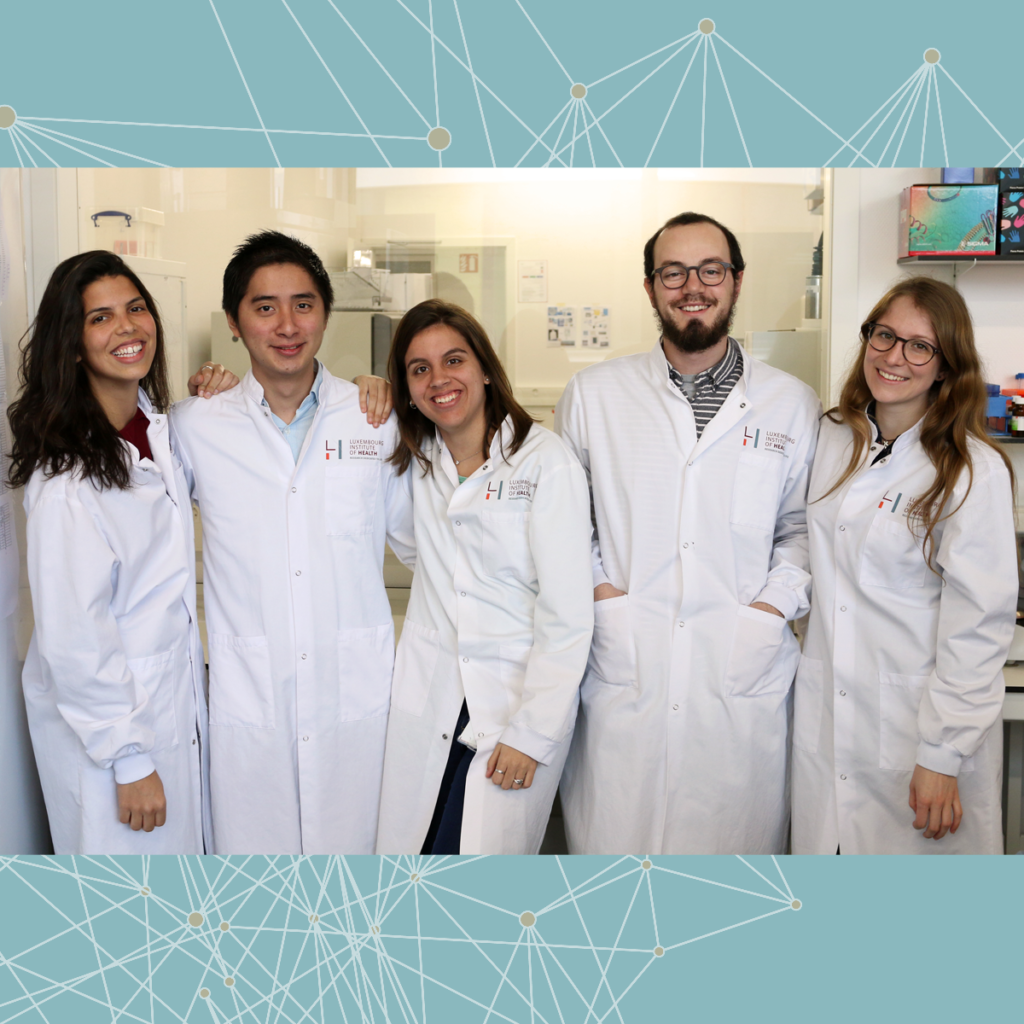

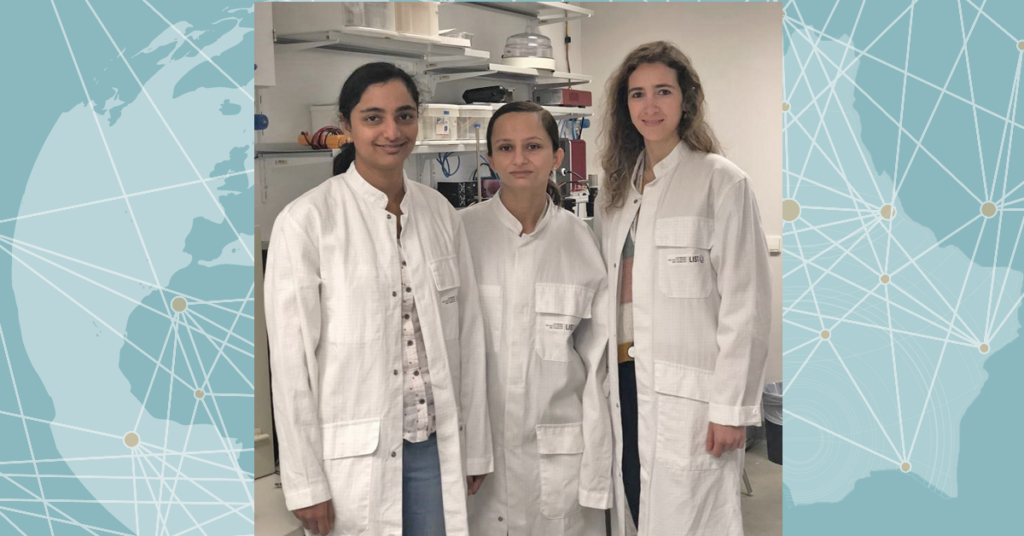

At KU Leuven, Luxembourg national Jill Kries is part of a research team driven by understanding how cognition and brain structure develop over time in language-related disorders and how this knowledge can be applied in a clinical or educational setting. We take a closer look at the work of the young team.

How does the brain develop when children learn how to read? How does the brain change after a stroke? These questions refer to very different spectrums of language – what they have in common: to answer these questions, an understanding of how language manifests in the brain is needed.

This is the common thread across the projects of a young research group based at KU Leuven, which includes AFR PhD grantee Jill Kries.

“On the one hand, our research team wants to know how the brain develops when children learn how to read and whether early training with tablet-based applications can help children that are likely to struggle with reading (dyslexia),” the team explains.

Despite the development of evidence-based reading interventions, many dyslexic readers do not attain the reading level of their peers. This could be explained by the dyslexia paradox: the most effective period for reading therapy is in kindergarten or first grade. As a dyslexia diagnosis is only given after years of reading instruction and remediation (from second grade onwards), the opportune window for reading therapy has passed.

In the context of dyslexia, the group also wants to understand the interplay between family risk of dyslexia and other known risk factors.

A better way to diagnose aphasia

“On the other hand, we are interested in how the brain changes after a stroke. Predicting the recovery path of a stroke patient could, for example, inform speech-language pathologists on therapy goals,” the team explains.

Aphasia is an acquired language disorder that impairs the communication skills, mostly happening to about 1 in 3 people who have had a stroke. While there is some recovery, most people experience language difficulties for the rest of their lives.

As a stroke can occur in different brain areas, different persons with aphasia can have different symptoms: difficulties with speech understanding, production, reading or writing. The challenge: defining the underlying deficit from which these symptoms originate – a deficit in auditory, phonological or semantic processing.

The current diagnosis tool here are behavioural language tests, but these take a lot of time and can be biased by related cognitive problems. In order to provide targeted therapy and improve recovery outcomes, a more efficient and objective way of diagnosing aphasia is needed.

Aside from the clinical and educational applications, the group’s work also contributes to more theoretical scientific questions, such as how children and adults process different aspects of language – and where in the brain this happens.

Below we take a closer look at the work of team members Jill Kries, Klara Schevenels, Lauren Blockmans and Femke Vanden Bempt and their research.

Wants to understand better the brain’s mechanisms of speech processing in persons with aphasia and ultimately create a new diagnostic tool based on neural responses

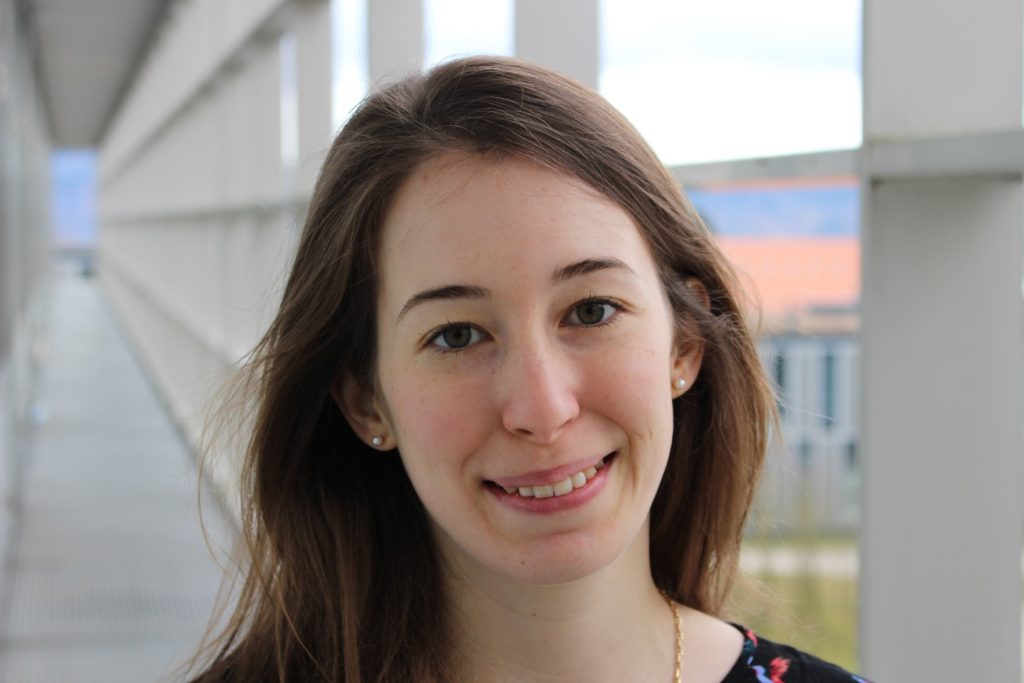

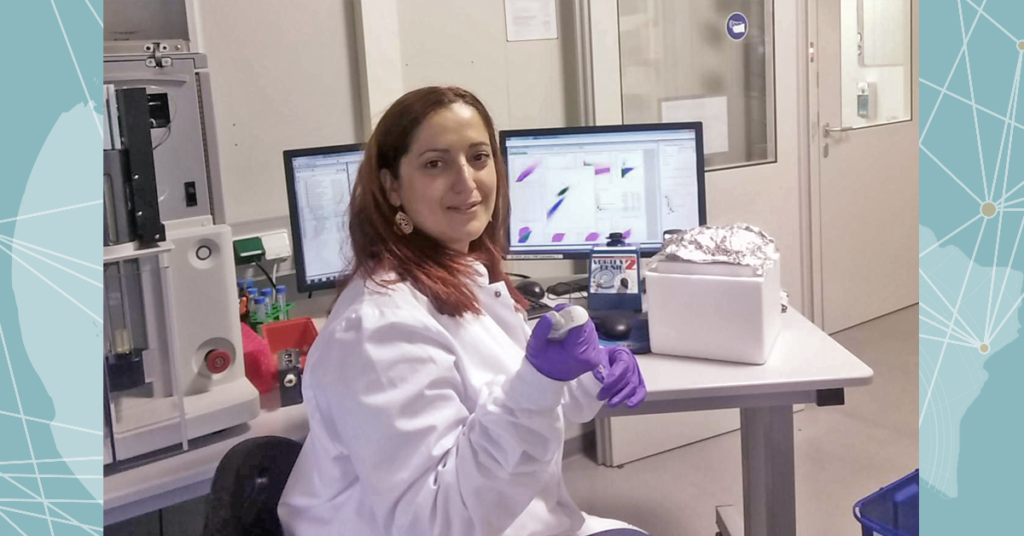

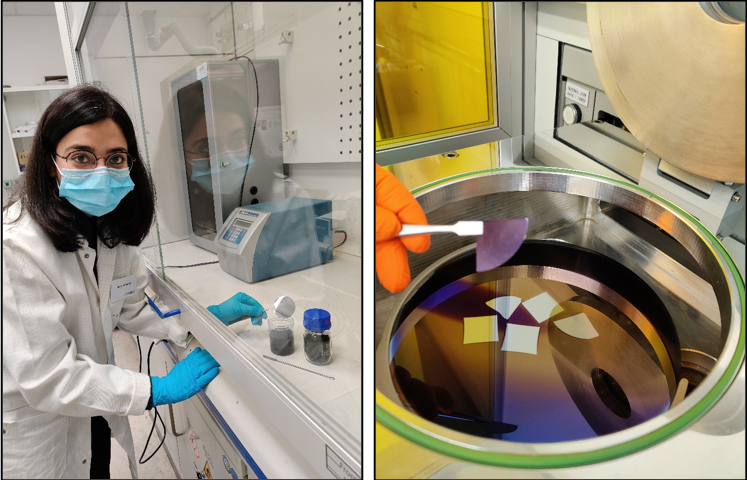

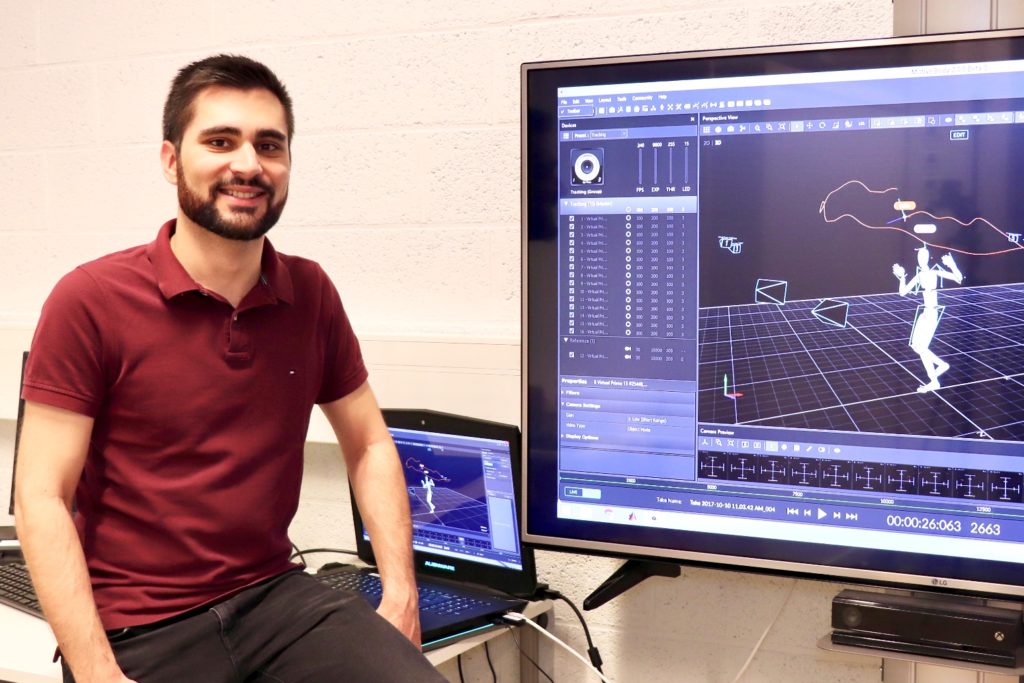

Jill Kries, 2nd year PhD

Nationality: Luxembourg

Your research focuses on improving the diagnosis of aphasia, a language disorder that mostly occurs after a stroke. How do you approach this research?

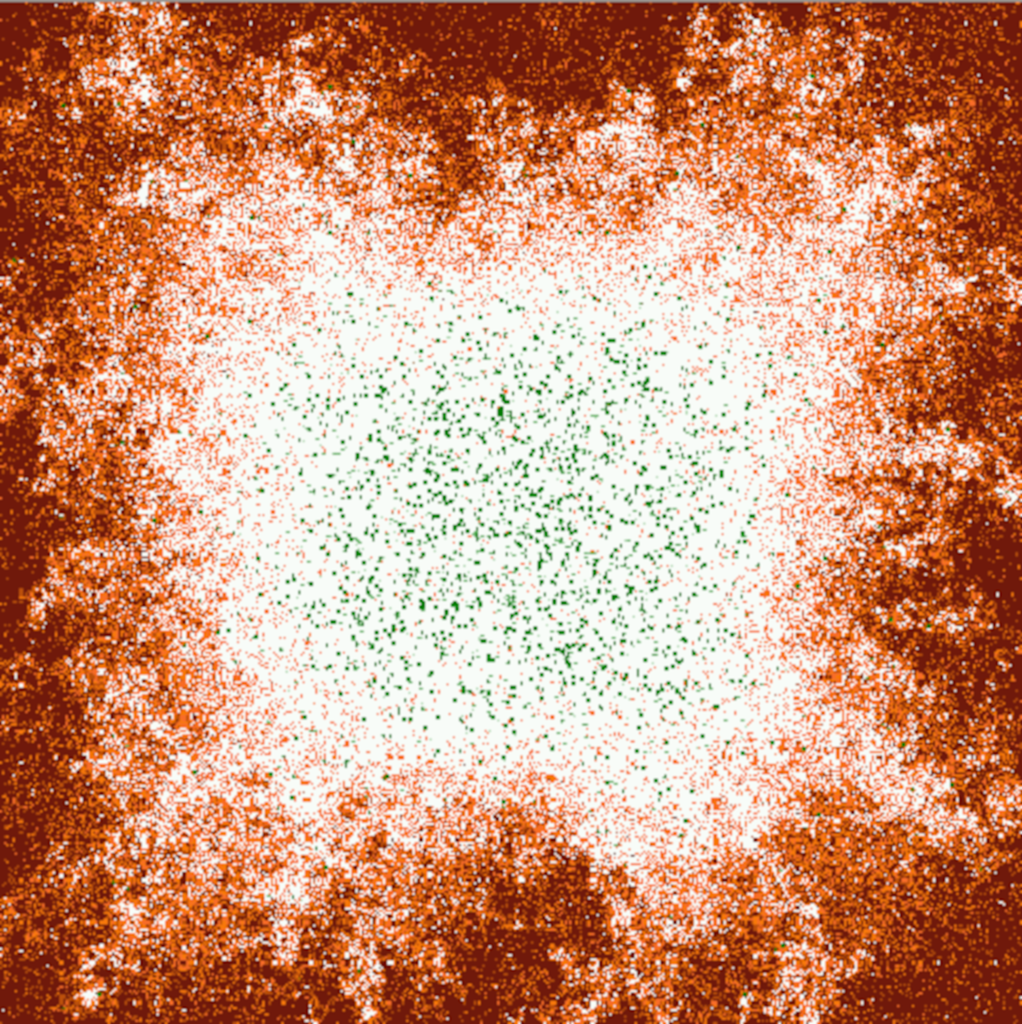

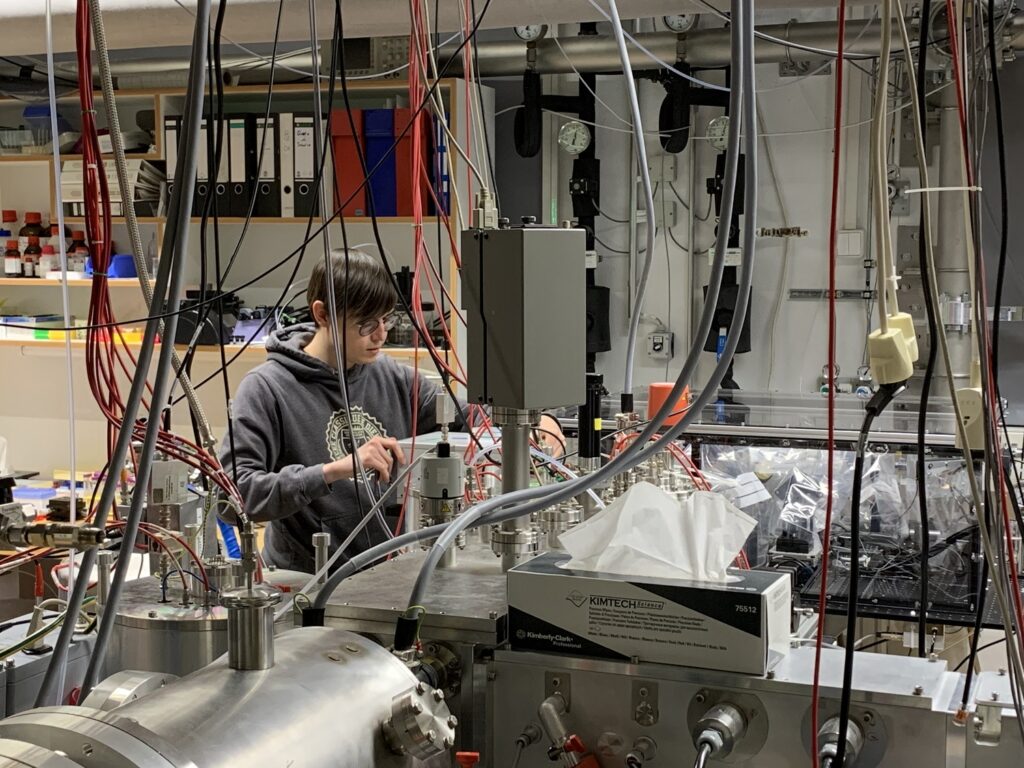

“We are using a neuroimaging method called electroencephalography (EEG) to unravel the underlying causes of speech processing problems in aphasia. In the long term, the aim is to develop a neurodiagnostic measure for aphasia.

“The work of the BrainSTORM group aims to understand which brain mechanisms cause developmental and acquired language disorders, such as dyslexia or aphasia. Furthermore, we use this knowledge to investigate aspects of diagnosis, intervention and recovery of these disorders.”

Why did you become a researcher – why this project?

“During my studies in neuropsychology at Maastricht University, I wrote my master thesis about the brain mechanisms during speech production. Next to the research internship, I also did a clinical internship at the university hospital in Aachen where I tested and diagnosed cognitive problems in patients with for example dementia, Parkinson’s disease and aphasia.

“After these positive experiences, I decided to look for a research project that would combine both aspects: working with patients and conduct research about language and communication.

“When I came across the project proposed by prof. Maaike Vandermosten, it was the perfect match. The lab and research group at KU Leuven offer a unique training environment for early-career researchers.”

What impact do you hope your research will have?

“I hope that my PhD project will lead to an objective and less effortful method for diagnosing patients with aphasia. Moreover, I hope my research will lead the way for further investigations on underlying brain mechanisms of speech processing in people with other communication disorders as well, for example fluency disorders or autism.

“Understanding these mechanisms could eventually lead to new therapy methods, brain-computer interfaces and many more applications helping the affected people to communicate in everyday life.”

“I feel inspired by many people that I have met during my studies and career:

- Dr. Joao M. Correia, who supervised my research internship and master thesis, introduced me to the world of language and communication research. He has a unique way of explaining complicated methods and at the same time keeping an eye on the bigger picture. With his passion for innovative and creative language research, he triggered my interest for cognitive neuroscience of communication.

- Prof Dr. Victoria Leong, whom I met at the Childbrain conference in 2019, is investigating neural synchronybetween primary caregivers and infants in a very innovative way. Her talk at the conference was captivating and inspiring, and I had a stimulating conversation with her about her research and presentation skills.

- Prof Dr Pascale Engel de Abreu from the University of Luxembourg is doing research about multilingual language development and learning and cognition in families with a lower socio-economic status. Moreover, she developed literacy interventions for young children. I feel very inspired by her research focus on the inclusion of language-minority children.”

Wants to improve the prediction of language recovery in stroke patients by considering risk and protective neural and cognitive factors.

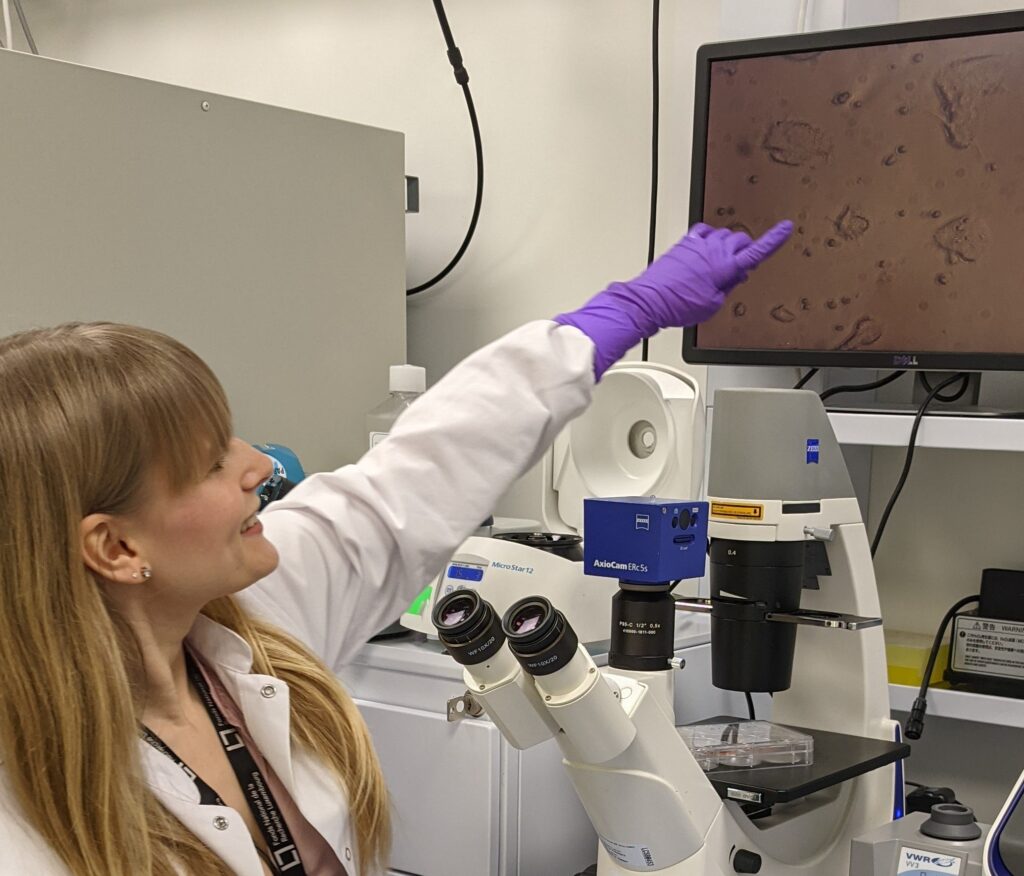

Klara Schevenels, 3rd year PhD candidate

Nationality: Belgium

Around 1 in 3 stroke survivors experience aphasia. Can you elaborate on your research in this area?

“Aphasia severely affects the well-being and daily functioning. In the first months after stroke there is some recovery, however, most persons experience language difficulties for the rest of their life. For the patient and their family, it is important to know whether, when and how they will recover, so that they can make plans for their future life.

“Information on the prognosis of the patient is also useful for the speech-therapist to maximize the recovery potential.

“Many researchers have already tried to predict language recovery in individuals, based on patients’ initial language performance and on details on their brain damage. But this information is not sufficient to make reliable predictions.

“I help investigate what kind of information would improve the prognosis of language in these patients. We try to extend the focus from “what’s wrong” to “what’s right”: from the brain lesion to intact brain structures and connections that can support language; from language problems to other cognitive abilities that can help in re-learning language.”

Why did you become a researcher – why this project?

“I have always been amazed by the brain and its influence on our behaviour. After graduating as a Speech and Language pathologist, I started doing clinical work and learned the importance of a multidisciplinary approach and evidence-based practice.

“However, I missed being more involved in research and working with neurological speech and language disorders. That is when I contacted the head of our current lab, Maaike Vandermosten, and she gave me the opportunity to start working on the aphasia project. I love the combination of the social aspect, medical sciences and the technical approach in this research!”

What impact do you hope your research will have?

“I hope to contribute to a reliable long-term prognosis for aphasia immediately after stroke. This is not only important for the patients and their family: Early identification of bad responders to a specific treatment would allow therapists to select a more appropriate or intensive language treatment or an alternative intervention method.

“By delivering effective interventions early, patients receive help in the time frame within which it matters the most. In addition, I hope our work will contribute to the understanding of brain plasticity throughout language recovery after stroke.”

- “Cathy Price: As a professor and researcher, she teaches and studies language in the human brain. Part of her work also focuses on recovery after neurological damage such as stroke. She and her team set up a major dataset aimed to explain and predict language outcome after stroke in a more automated manner. This kind of initiatives are of major importance to move our field forward!

- Stephanie Forkel: Her PhD work on mapping variability in certain brain connections to predict language recovery in stroke patients was an important inspiration for our research. I admire her for her extensive knowledge on the brain’s anatomy, her skills in the analyses of MRI data mapping these white matter connections and her efforts to spread this knowledge to other researchers and clinicians.

- Maaike Vandermosten: As the head of our BrainSTORM lab, she is the person that influenced me in the most direct manner. Every day she manages to inspire us with her positive mindset and enthusiastic way of conducting research!”

Wants to unravel the effects of heredity on dyslexia at both the behavioural and the brain level.

Lauren Blockmans, 2nd year PhD candidate

Nationality: Belgium

The focus of your project is on family risk / risk factors for developing dyslexia. Can you elaborate?

“For children that have a family risk of dyslexia (meaning at least one close relative has dyslexia), we know what behavioural factors increase the risk of developing dyslexia. Well known risk factors include letter knowledge and the ability to play around with sound structures of words (e.g. rhyming). However, to predict whether a child without a family risk might develop dyslexia, it is not clear if the same risk factors apply.

“In my PhD project, we aim to understand the influence of having a family risk on the known risk factors. This contributes to our understanding of the development of language related skills in young children.

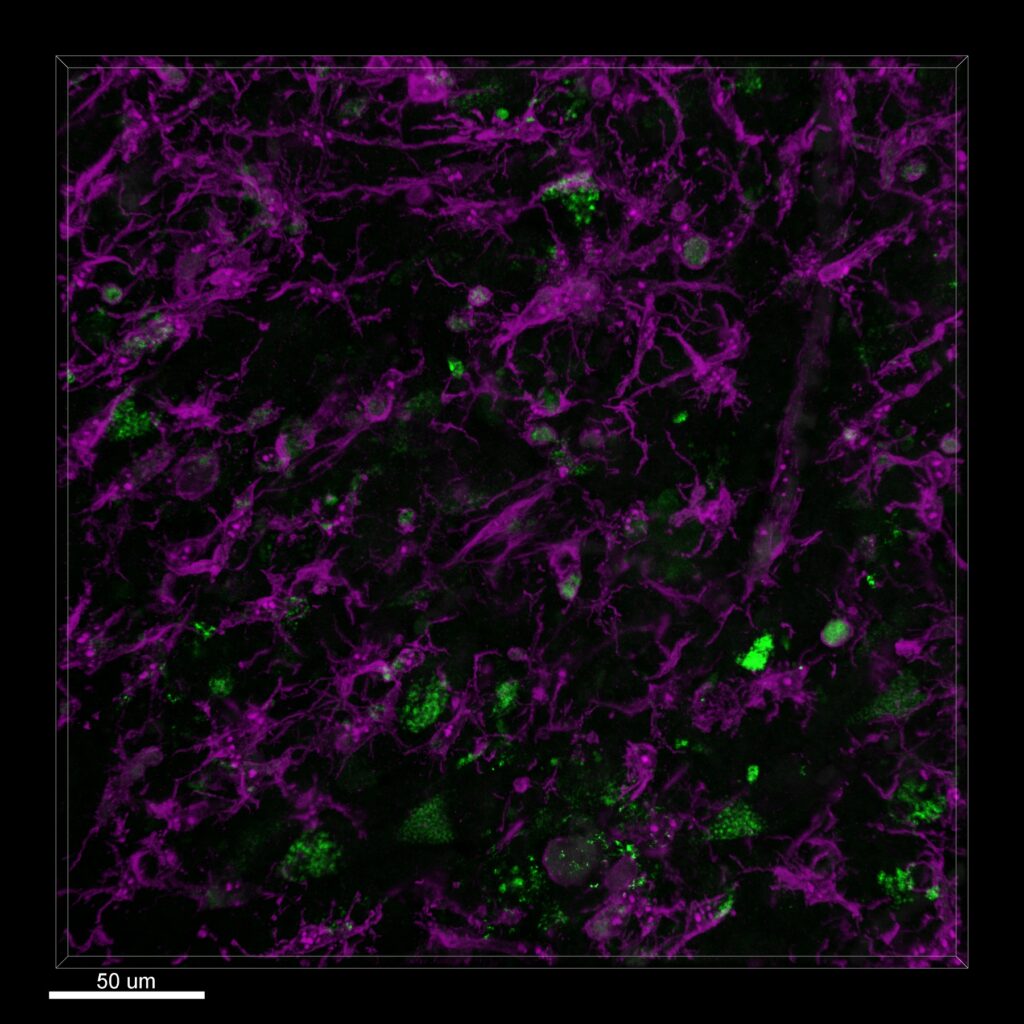

“Moreover, by looking at the connections between important brain regions, we want to know if this also is reflected in a different underlying cause of dyslexia.”

Why did you become a researcher – why this project?

“During my master of Speech-Language Therapy and Audiology, I was very much attracted to the scientific focus of our courses and to the process of conducting research (when writing the master’s thesis).

“Additionally, during my internship in a diagnostic centre for children with reading problems I learned that bringing scientific findings into practice is very important. These insights sparked my interest in research. This specific project really felt like the perfect combination of both.”

What impact do you hope your research will have?

“On the one hand, the focus on behavioural profiles of children with dyslexia could inform educational practices. Apart from children with a family risk, children without a family risk could also be identified as at risk for developing dyslexia.

“Existing tablet-based screening instruments could be adapted to fit kindergarteners with and without family risk.

“On the other hand, findings at the brain level might shed further light on the underlying causes of dyslexia and potential protective factors. This way, my research work could be valuable for the clinic and research.”

“I feel inspired by many scientists, such as:

- Nadine Gaab: she is an example of a strong woman in dyslexia research (among many others!). She is also very oriented towards the practical application of her scientific work into education.

- Elsje van Bergen: from an interview of the Dutch Research Council, I learned that she encountered difficult parts in her scientific career but showed a lot of perseverance to get where she is now.

- Victoria Leong: she was one of the speakers on the first conference I ever attended during my PhD. I felt very inspired by her exceptional presentation skills and passion about her work.

- Brian Nosek: he is the co-founder of Center for Open Science and advocates strongly for transparent science and reproducible research. This is becoming increasingly important (and rightfully so) and it was partly his view on open science that pushed me to pre-register the analyses of my first paper.”

Investigates the cognitive impact of preventive gaming in kindergarteners at risk for dyslexia.

Femke Vanden Bempt, 3rd year PhD candidate

Nationality: Belgium

In more detail, what is the focus of your research on dyslexia?

“Developmental dyslexia (DD) is a neurodevelopmental learning disorder, which is characterized by severe and persistent problems with accurate and fluent word decoding and spelling. It is widely demonstrated that DD is linked to difficulties with the awareness of the sound structure in a language. Moreover, evidence exists that reading skills in individuals with DD can be improved with sound awareness and letter-sound coupling exercises (the so-called phonologically-based intervention programs).

“However, despite the development of evidence-based reading interventions, a sizeable number of dyslexic readers do not attain the level of their typically developing peers. This is possibly explained by the dyslexia paradox, which states that the most effective period for reading therapy is in kindergarten or first grade, whereas a diagnosis of dyslexia is only given after several years of reading instruction and remediation (from second grade onwards).

“Thus, by the time the diagnosis of dyslexia is given, the most sensitive period for remediation has passed. In order to overcome this paradox, intervention needs to take place earlier in time, even before a clear diagnosis is assigned. My PhD focuses on the cognitive impact of a preventive phonologically-based tablet intervention in pre-reading kindergarteners at cognitive risk for dyslexia. This research contributes to the understanding of how to effectively prevent reading failure.”

Why did you decide to go into research, and why did you choose this research group?

“I wanted to conduct dyslexia research because of two main reasons. Firstly, while obtaining my Master in Speech and Language Pathology, I followed a very interesting course on the state of the art in the research field of learning disabilities, which aroused my interest in studies of typical and atypical reading development. Secondly, the Master thesis that I wrote discussed the cognitive processes of foreign language learning.

“I was so captivated by the topic, so motivated to work on my own research project and so inspired by the enthusiasm of my supervisor (the head of this research group) with regard to conducting research, that I decided to become a researcher of the BrainSTORM research group, if I would ever have the chance.”

What impact do you hope your research will have?

“Already before the start of reading education (i.e. in kindergarten), children at risk for dyslexia perform lower on reading-related tasks compared to typically developing children. Moreover, this gap becomes wider over time. Therefore, it is of high relevance to develop and investigate the impact of early preventive interventions for children who are at risk for reading failure.

“With this PhD, I hope to get a clearer understanding of the underlying skills which should be targeted during reading intervention.”

“I feel inspired by many scientists, such as:

- Prof. Dr. Maaike Vandermosten: She is the leader of our BrainSTORM research group and she was the supervisor of my Master thesis. With her enthusiasm, kindness and passion for research, she inspired me to become a researcher too.

- Prof. Dr. Bart Boets: He is a Professor at KU Leuven at the Department of Neurosciences and conducted many studies regarding the cognitive and auditory perceptive predictors of developmental dyslexia. Among other things, his findings form the basis of our present intervention study.

- Prof. Dr. David Purpura: David Purpura is a professor at the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at Purdue University. I attended three of his research seminars at KU Leuven about story interventions, aimed to increase mathematical language skills. I was very inspired by his talks and the intervention story books, which were particularly created within the framework of his research.”

About Spotlight on Young Researchers

Spotlight on Young Researchers is an FNR initiative to highlight early career researchers across the world who have a connection to Luxembourg. The campaign is now in its 4th year, with 45+ researchers already featured. Discover more young researcher stories below.

More in the series SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG RESEARCHERS

- All

- Cancer research

- Environmental & Earth Sciences

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Information & Communication Technologies

- Law, Economics & Finance

- Life Sciences, Biology & Medicine

- Materials, Physics & Engineering

- Mathematics

- Research meets industry

- Spotlight on Young Researchers

- Sustainable resource mgmt

- Women in science