Anja Leist wants to find out how to resist the decline of our cognitive abilities in old age. Her international research has already achieved a first result: improving education helps prevent problems occurring decades later.

Old age comes with physical and mental challenges, including cognitive decline, dementia and ailments such as Alzheimer, which have few, if no cures. What if we could do something about it in childhood? That is what Anja Leist believes, a public health professor at the University of Luxembourg.

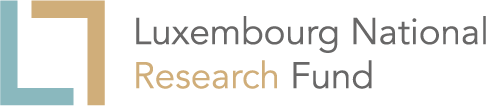

“Sociological and psychological factors play a huge role in our cognitive reserve, meaning our capacity to resist the deterioration of our mental abilities,” explains Anja Leist. So far, scientists have identified factors explaining half of the differences observed in the population. A further 30% could be traced to factors such as education, social isolation, cardiovascular risk and midlife depression – much more than genetics, which accounts only for around 7%. “This is good news because they do represent huge potentials in terms of preventing the onset of decline later in life.”

The burden of unequal education

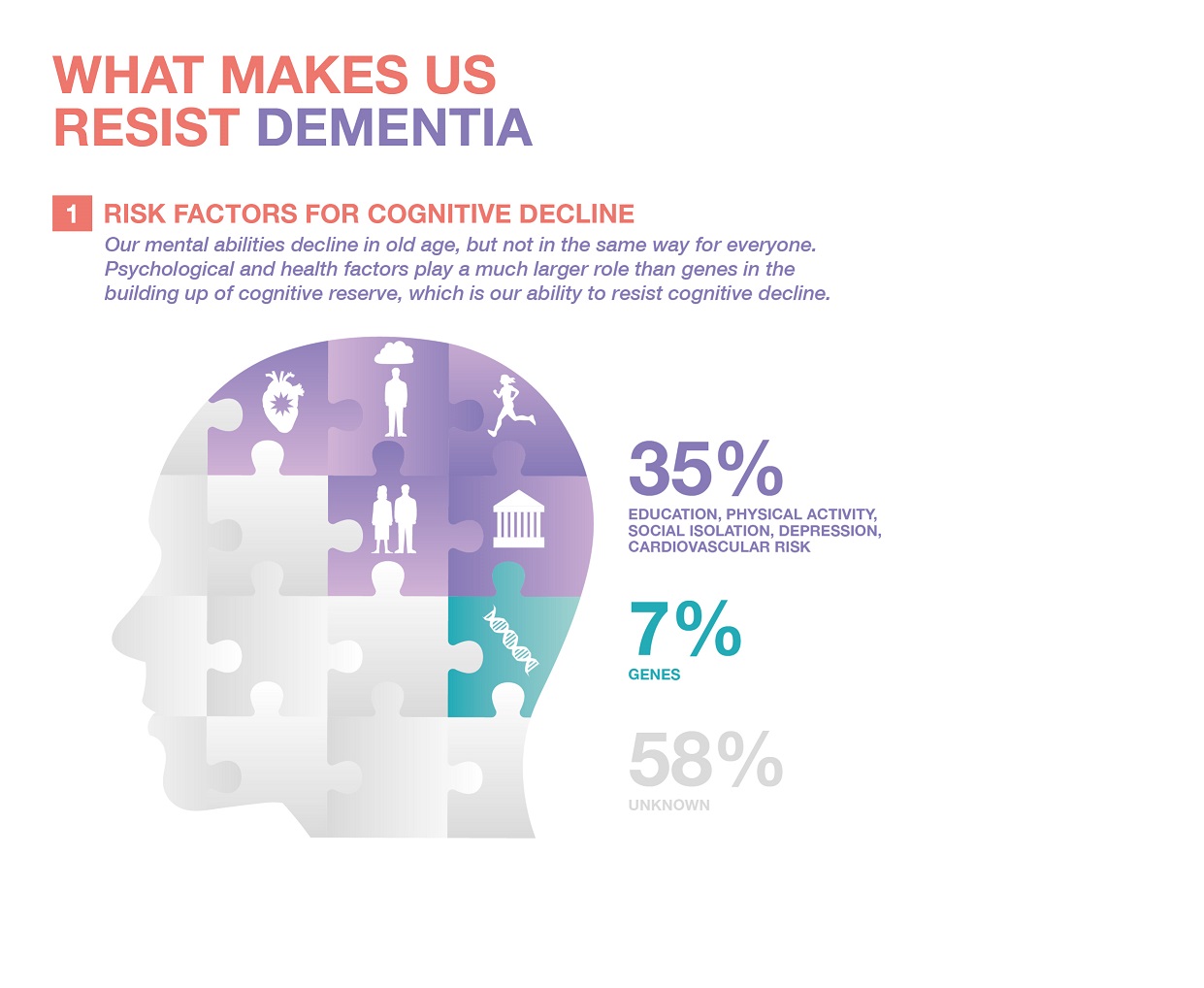

The researcher and her colleagues found out that reduced access to education as a child decreases that individual’s cognitive reserve in later years, a result based on their analysis of a large survey made of more than 40 000 people in Europe.

The participants were followed over decades, providing information about their health, employment, family background and education, and performing tests every few years to measure their cognitive abilities such as memory or verbal fluency years. The international team looked for associations in the data, including country-level socioeconomic factors such as GDP, human development index or education inequalities.

“All these parameters are tightly intertwined. The goal of our research is to untangle them as much as possible. Our analysis revealed the importance of education: all other things being equal, cognitive reserve at greater age is lower in countries having larger inequalities of education opportunities. The latter measures how hard it is for children to attain a higher level of education when their parents had left school early.”

“Education inequalities can arise from subtle effects, including the unconscious biases we all have. In Luxembourg, for instance, parents indicate their profession on school documents. While this information has nothing to do with the actual performance of the children, it might still have an invisible influence on the way they are assessed.”

Higher risk for women

The effect of education on cognitive decline is, in fact, driven by one subgroup: women who left school early. Their cognitive decline at old age is greater for country showing greater educational inequality. Anja Leist stresses that the school attendance counts, and not only the opportunities school favours or hinders for the subsequent years:

“Of course, having a fulfilling job which stimulates our brain will increase our cognitive reserve over the years. But studies could disentangle the two factors. They compared states in the US which changed the obligatory school system, making it last longer. This did not really influence the type of employment which people had later, but one could observe an increase of cognitive reserve years later, showing that the length of education counts.”

These results suggest that increasing educational opportunities for children growing up in less educated families could represent a good investment in the future, as it would both reduce the burden for those affected and their families generated by dementia later and its substantial societal and economic costs.

Artificial intelligence meets sociology

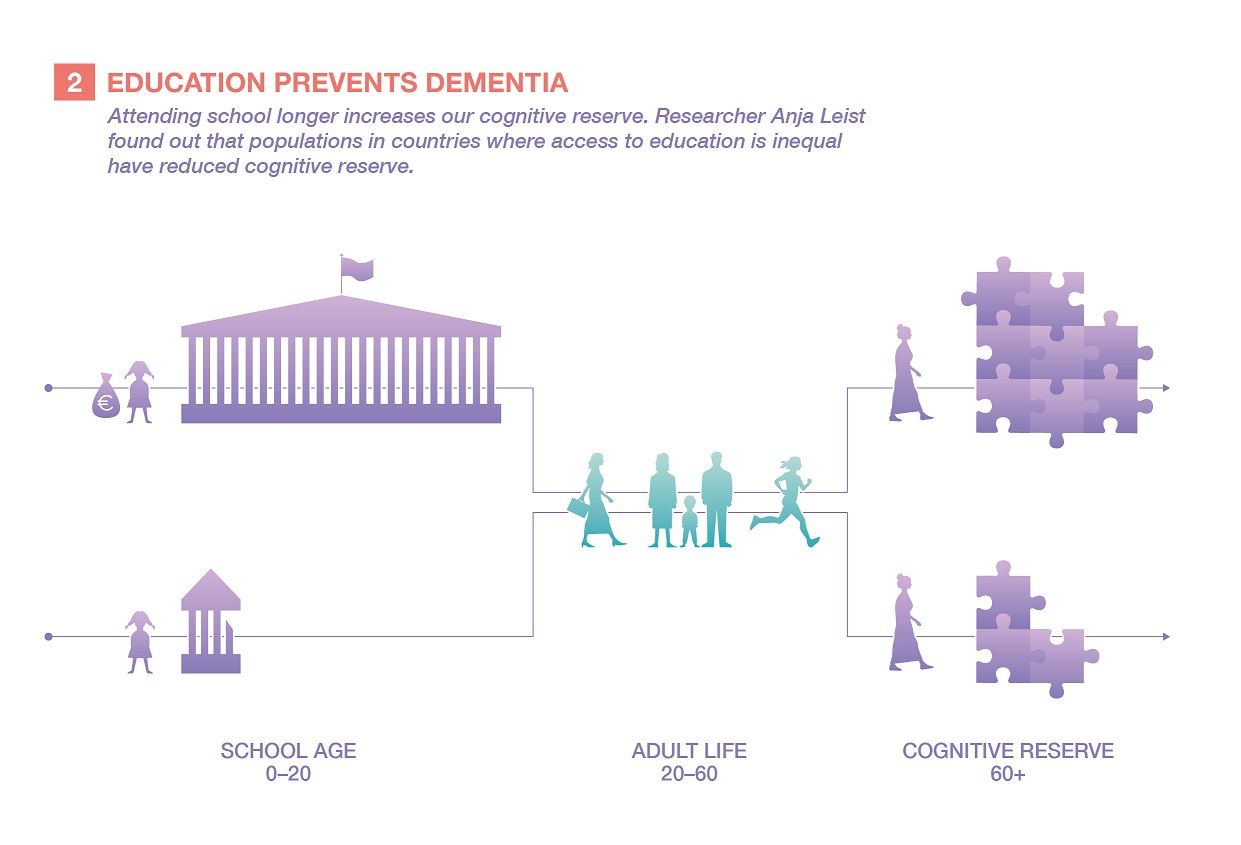

But these massive population surveys have not yet revealed all their information. To study the data in more detail, Anja Leist is turning to machine learning, a technique of artificial intelligence often used to analyse Big Data.

“Our aim is to find out whether one intervention – such as encouraging fitness activities amongst middle-aged women – really does prevent dementia. In an ideal study, one would divide participants into two groups: the first one going to a fitness centre once a week, the other staying at home. While this would allow for a very clear comparison, it would be too unethical to be made in practice because it would prevent a healthier lifestyle bringing proven benefits in many health aspects.”

Leist’s idea is to use vast amounts of data to simulate such comparisons.

“We can use machine learning algorithms to identify within survey pairs of persons who are practically identical for all parameters such as age, education, profession, etc. except that one of them goes to the gym, the other not. This will allow us to make what we call a causal analysis and answer the question: what would have happened to the second person if they had behaved like the first one and had started going to the gym?”

Ultimately, such analyses could help identify which prevention measure has a higher impact on which population group and help target campaigns towards the population group at risk.

“So far, we have no convincing treatment against dementia,” says Anja Leist. “I believe any promising way to prevent it should be looked at – including building educational systems that give equal opportunities to children from all backgrounds.”

More information

About the European Research Council (ERC)

The European Research Council, set up by the EU in 2007, is the premiere European funding organisation for excellent frontier research. Every year, it selects and funds the very best, creative researchers of any nationality and age, to run projects based in Europe. The ERC offers four core grant schemes: Starting, Consolidator, Advanced and Synergy Grants. With its additional Proof of Concept grant scheme, the ERC helps grantees to bridge the gap between grantees’ pioneering research and early phases of its commercialisation. https://erc.europa.eu

The European Research Council, set up by the EU in 2007, is the premiere European funding organisation for excellent frontier research. Every year, it selects and funds the very best, creative researchers of any nationality and age, to run projects based in Europe. The ERC offers four core grant schemes: Starting, Consolidator, Advanced and Synergy Grants. With its additional Proof of Concept grant scheme, the ERC helps grantees to bridge the gap between grantees’ pioneering research and early phases of its commercialisation. https://erc.europa.eu

More features in this series

The ERC series is written by Daniel Saraga. The purpose of this ERC series is to showcase the high quality of research in Luxembourg, and how it is also attracting prestigious international funding.